He told himself he was too pampered, too spoilt by civilization, ever to inhabit nature again; and that made him sad in a not unpleasant bitter-sweet sort of way. After all, he was a Victorian. We could not expect him to see what we are only just beginning – and with so much more knowledge and lessons of existentialist philosophy at our disposal – to realize ourselves: that the desire to hold and the desire to enjoy are mutually destructive. His statement to himself should have been, “I possess this now, therefore I am happy; instead of what it so Victorianly was: “I cannot possess this forever, and therefore I am sad”. The French Lieutenant’s Woman, Chapter 10, John Fowles (1969)

Carpe diem (or YOLO if you’re Rihanna) – a timeless mode of thought?

Arguably modern attitudes to historical artefacts remain Victorian; fragility, rarity and legacy count for much. Or is it just human nature to infer a state of sanctity?

Does protection prevent real enjoyment by limiting handling, transportation, wider inspection? A missed opportunity for closer contact with something that has experienced the past and is witnessing the present.

This is well-trodden ground, and something that is rightly being challenged, if only for the purpose of pushing more ingenious ways of “engagement”.

But what interests me is when this sanctity is divined? When does something pass into the realms of relicdom?

I pondered this recently with the death of my aunt (bastard cancer).

The inevitable divvying up of possessions followed, although to a lesser degree, my aunt having completed much of this task herself. The horror of accepting (jewels, coffee sets), I cannot accurately describe.

My mother has largely been the recipient of clothes; quite literally stepping into her big sister’s shoes.

The rest? “Charity shop, I s’pose”, shrugged my uncle. Then, “They don’t suit me”. Finally, “They’re just things”.

On a surface level possessions, artefacts, are not a person, so what do they matter?

They matter to living memory and future interpretation. Providing a link between events, conversations, encounters, whilst providing the scope for future persons to guess at these.

I am an acute mixture of these. Having lost my dad at a young age I can’t always be certain what is fact (my genuine memories) or fiction (what I have been told since). I’m not saying that these are mutually exclusive, but the uncertainty is infuriating.

Yet my response to objects is something apart. There is no doubt.

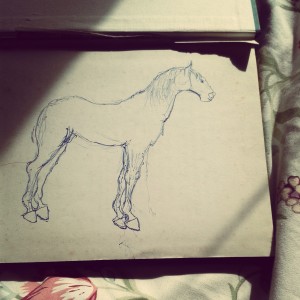

This is his sketch, unearthed, albeit from 1967 – I see him drawing, pen in hand.

The worn patch on the right-side arm of a chair – there, he’s resting his head in his right hand whilst watching telly.

For this reason, I value objects. I cherish them. Things that have meaning to just a few. But I don’t claim exclusivity. The potential for future speculation, wildly inaccurate guesses, thrills me.